Imagine being told that someone you love is dying. Not someday. Not eventually. Soon. And then imagine hearing the words that change everything: “A transplant could save them — if a living donor is found.”

At that moment, the question stops being theoretical. It becomes personal. Terrifying. Irreversible.

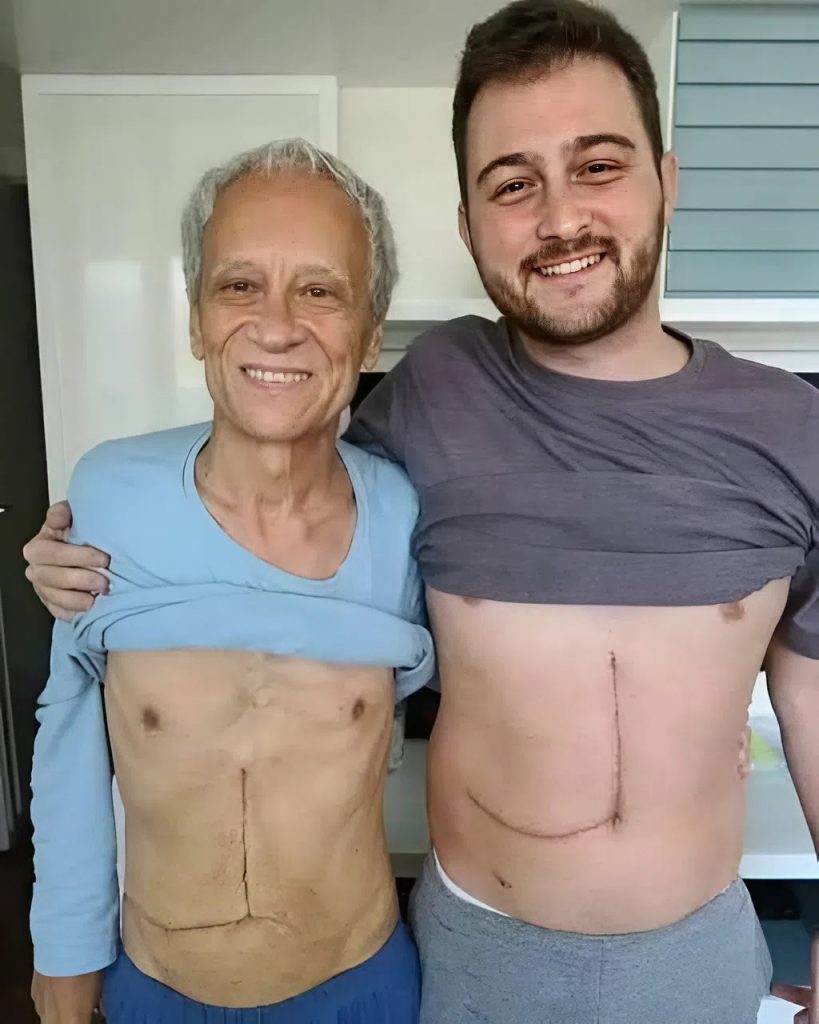

Living liver donation is often presented as a medical miracle — a triumph of modern science and human compassion. And in many ways, it is. But beneath the hopeful headlines lies a reality far more complex, painful, and dangerous than most people are prepared to face.

This is not just a surgery.

It is a life-altering gamble.

Why the Liver — and Why a Living Donor

The liver is the only human organ capable of significant regeneration. Surgeons can remove up to 60 percent of it, and in time, it can regrow. This biological rarity makes living donation possible and, in countries with long transplant waiting lists, increasingly common.

But regeneration does not mean immunity. Removing part of a liver from a healthy person is one of the most invasive procedures in modern medicine. It involves hours on the operating table, massive surgical trauma, and the very real possibility that two lives are put at risk instead of one.

That is the part rarely emphasized.

Who Becomes a Donor — and Under What Pressure

Most living liver donors are not strangers. They are parents trying to save a child. Siblings watching each other fade away. Spouses facing the unthinkable. The decision is often made in emotional crisis, not calm reflection.

Doctors insist on informed consent, psychological evaluations, and medical screening. Yet no form can fully measure the silent pressure of love, guilt, and fear. When the alternative is death, “choice” becomes a fragile concept.

Many donors later admit they did not fully grasp what they were agreeing to — not because they were careless, but because the human mind struggles to imagine permanent consequences when time is running out.

The Risks That Statistics Don’t Explain

On paper, the numbers look reassuring. Low mortality rates. Acceptable complication percentages. But statistics do not scream in pain at 3 a.m. Statistics do not struggle to climb stairs months after surgery. Statistics do not wake up wondering if their body will ever feel normal again.

Living liver donors may face:

severe infections and internal bleeding

bile duct injuries

blood clots and organ failure

chronic pain and fatigue

long-term physical limitations

Recovery is not measured in days or weeks. For many, it takes months. For some, it never fully ends.

And when complications occur, the donor — once perfectly healthy — becomes a patient with no medical necessity other than having tried to save someone else.

The Psychological Wounds No One Prepares You For

The emotional aftermath can be as devastating as the physical one. Donors often report anxiety, depression, and identity crises. Their bodies have been altered permanently, and their sense of safety is gone.

The most unbearable outcome is failure. When the transplant does not succeed and the recipient dies, donors are left carrying an invisible burden: “I gave everything — and it wasn’t enough.”

There are no words for that kind of grief.

Is There a Reward?

Yes — but it is not simple.

For donors whose recipients survive and recover, the reward is profound. Seeing life return to someone who was fading can bring a sense of purpose few experiences can match. Many describe it as a moment that reshaped their understanding of existence, mortality, and love.

But even then, the donor’s sacrifice often fades from public memory, while its consequences remain etched into their body.

Heroism or Systemic Failure?

Living liver donation raises uncomfortable questions. Is it the ultimate act of human compassion — or a desperate solution in a world where deceased organ donation remains insufficient?

Perhaps it is both.

What is certain is this: romanticizing living donation does a dangerous disservice. It silences doubt. It minimizes risk. It turns a deeply personal medical decision into a moral expectation.

Before You Say “Yes”

No one is obligated to give up a part of their body — not for family, not for love, not for hope. Choosing not to donate does not make someone weak, selfish, or heartless. It makes them human.

The liver may regenerate.

A damaged life may not.

Living liver donation deserves honesty — raw, uncomfortable, and complete. Because behind every “successful transplant” headline is a donor whose life will never be exactly the same again.